“Chico! Can you hear me? Are you there? We’ve got a serious problem. All the waterproofing has failed—the flood test didn’t hold. You need to come quickly.”

Chico looked at his watch. 19:00 was just around the corner. The last thing he wanted was to drive to Rosh HaAyin now. Why had they agreed to take this job at all? The balcony was old and trouble-prone. Even after they’d lifted all the tiles, nothing down below was clear: patches of concrete cobbled together over the years, and all sorts of improvised sealants trying to plug holes on the cheap.

How much did they even pay us for this? he wondered. They shouldn’t have said yes. It was obvious this was the kind of job that would deliver headaches—and very little income. The trouble was, they were already in it, and there was no backing out now.

“I’m on my way,” he answered.

“Come fast,” said the voice on the other end. “Blessed rains are pouring into the living room.”

Chico headed down to the car, started the engine, and pulled out. Waze showed 45 minutes—which meant the real work would only begin after dark. On the way he disconnected from work, from tar, from blocks, from wet sand. His eyes were open—but he began to dream.

His mind carried him far away: to the middle of a forest, on a small grassy mound, facing a makeshift stack of speakers and a DJ table. Binyamin—known as Benji—had taken command of the music and was steering dozens of dancers before him. They threw their arms high toward the sky, bounced side to side—and looked like they were in a half-religious trance. Some were truly religious; others were “on the spectrum,” each in his place.

At another station they handed out drinks. The budget was thin, and after the beers ran out they started cutting the vodka and arak with water. The dancers were happy anyway; you didn’t need to raise the alcohol content to reach the goal.

Chico watched the party from the side. It was the fifth time he’d managed to gather this crew and give the freedom-seekers a little joy in the middle of nowhere. He himself didn’t join them—his freedom was to watch them dance and create a small, alternative world for a few hours.

He’d landed at the first party almost by accident. Two friends from yeshiva told him that during bein hazmanim it was fine to loosen up: if the secular crowd goes to clubs and dances with girls—they’re allowed to rejoice too, just maybe without the girls. The first time he just watched from the side and tried to grasp what they wanted. They didn’t ask for much: driving beats, maybe spiced with Hasidic tunes; cheap alcohol; and above all a place to let go a little—far from everyone.

His challenge was to find those places. You can’t just stop in any forest or abandoned field. You need somewhere secluded enough that the party won’t be shut down, yet reachable even for guys cramming six or seven into rattling cars.

That was his specialty: find the spots, connect the music man and the drinks—and give everyone a 4–5 hour window outside this world. The concept held for nearly a year, but when the yeshiva’s head rabbi learned what Chico was doing in his spare time and where the boys were heading from time to time—he was furious. Chico sat calmly and made his case, but the rabbi wasn’t persuaded. He preferred they find their release in more supervised settings. “You can dance at weddings too,” he said. “Enjoy it there—and it’s even a mitzvah. No need to go into forests looking for adventures. You’re not like the seculars—you have fear of Heaven. ‘And in their statutes you shall not walk,’” he concluded.

Chico promised to retire from the parties. The tap shut off at once, and he returned to the study bench full-time. But he missed it constantly—especially that feeling of absolute freedom among the trees, in the middle of nowhere, far from everything.

“You have reached your destination,” Waze announced. Chico sighed, stepped out of the car, and hurried up the stairs to the flooded apartment. The homeowners waited with gloomy faces—and, mainly, a row of buckets. “It didn’t work,” the tired husband muttered. He knew a long night with his angry wife was still ahead.

“Yes, we’ll need to go deeper. I’ll plug the holes now and figure out how to beat these running waters. Don’t worry—we won’t leave you alone. We’ll go into this fight against the damp together—and we’ll win,” Chico tried to reassure them.

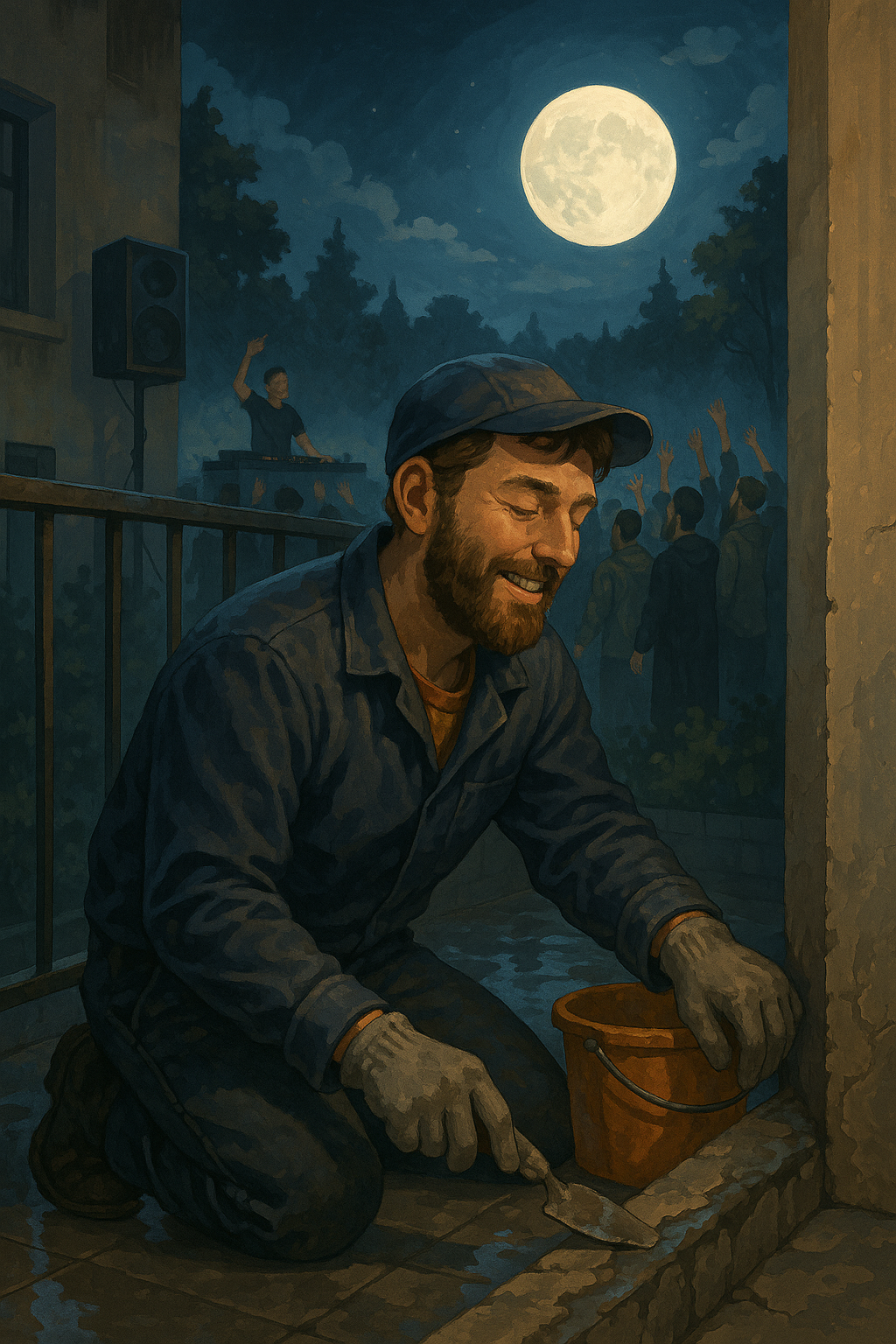

He cleared the water, climbed to the balcony, and hunted for the stubborn leaks. Suddenly the moon stood before him and bathed him in light—like in the famous story “The Shabbat Dress.” For a moment he wasn’t on a crumbling balcony, but back in the forest clearing—with the music and the freedom. For one heartbeat he was again Yissakhar, the yeshiva student, finding the missing feelings amid fifty boys dancing without pause. And for one heartbeat he smiled to himself: look— even on a shabby balcony with water running—I found, for a second, absolute freedom.